An Open Life: Interview with Maris Sants

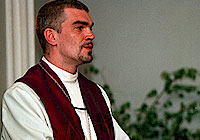

Maris Sants, mathematician, pastor and psychotherapist, was one of the very first openly gay public figures in Latvia. In June, he left Latvia for the more tolerant, gayfriendly environment of London. His openness in regard to his sexuality, and his willingness to speak out about LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender) issues, made him the center of a media frenzy for the past several years. In 2002 he was defrocked and excommunicated from the LELC (Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Church).

Maris Sants, mathematician, pastor and psychotherapist, was one of the very first openly gay public figures in Latvia. In June, he left Latvia for the more tolerant, gayfriendly environment of London. His openness in regard to his sexuality, and his willingness to speak out about LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender) issues, made him the center of a media frenzy for the past several years. In 2002 he was defrocked and excommunicated from the LELC (Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Church).

Since, he has worked as a pastor at the Open Evangelical Congregation, which was officially established after his excommunication from the LELC. For the past two years, his congregation has only been able to hold secret meetings. Despite Latvian society's constant attempt to crush this man, he has still managed to maintain a thriving private psychotherapy practise. City Paper met up with him before he left for London to discuss his reasons for leaving, and his general views of the LGBT situation in Latvia.

Why have you decided to leave Latvia?

Before I tell you why I've decided to leave, I should tell you why I decided to come out, because that is what immediately defined the role which I have played here. As I look back, I understand that I came out not because I wanted to fight, but because I just feel that it is right to be out. It is totally wrong to hide my love or my ability to love. If I had gone on like that I would be a hypocrite with everyone around me. One of the very reasons I came out was that I wanted to be completely open in my relationships with both women and men, and with the church congregation. My choice has essentially made me a victim. Being a homosexual pastor is something too exotic for people. For more than six years now, since I revealed my homosexuality, I have been living inside a war. I don't want to go on with this fight forever; six years is enough. This is one reason that I am leaving. The other reason is because the situation for LGBT people hasn't improved.

What will you do in London?

I want to continue working as a psychotherapist and hopefully I will also have a part-time position working as a pastor in the Anglican Church in London. These are just my dreams and aspirations right now. I am prepared to do any job until I can get myself established there.

Why now? Why didn't you leave after the 2006 Friendship Days, when the Pride Parade was actually banned by the Riga City Council, and protestors showed up at your church service on the scheduled day of the parade, armed with bags of their own excrement? You were one of the targets then; people threw waste at you, chased you, and shouted insults. Why didn't you leave after that?

There were two reasons. One was my responsibility to my congregation – our congregation – in Riga. After such an ordeal, it would have been as if I had left them in trauma. The feeling of defeat would have also been too overwhelming. Also, in those days I simply didn't have the resources to move.

Do you feel positive and optimistic about leaving, or are you leaving with regrets?

Of course I have mixed feelings because I will leave a lot of friends here. Also, I will dearly miss my family. My mother, who will stay here, is quite old, and I won't be able to help my daughter or son with their studies. There are also a lot of positive things about leaving. When I arrive, I'll be staying in a flat in Soho. Imagine living in Soho after Riga; the heart of London's gay community. On any street, I will be able to walk with my partner, hand in hand, and I won't need to hide anything!

You said that the LGBT situation in Latvia isn't improving as quickly as you would have liked. Could you talk a bit more about that?

On the one hand, the situation is improving very quickly, in that more and more people are coming out, and a growing number of people are also speaking about their sexual orientation in their homes. So it is actually improving invisibly, in families. Not everyone comes out, but many people do. Also, the gay community has developed enormously through these four pride marches. We can see mature, self-confident, self-respecting people who are able to speak for themselves. These are not only people in Mozaika (Latvia's main LGBT NGO), but other people who are unashamed of themselves, and feel that no religion can dictate their understanding of God. On the other hand, I see all of these politicians who make hate speeches. I see leaders of the churches who don't bring peace, which is actually a fundamental principal of Christianity. Instead, they split society by not allowing different opinions or democracy and discussions about controversial issues.

Even the Archbishop, Cardinal Pujats, wrote a letter to the Riga City Council saying that they should not allow the Pride march to take place. I believe that kind of action is completely wrong – not because I am on one side or the other, but because I believe that the Archbishop should not dictate to the state what should and shouldn't be done.

Is there anything that churches from abroad could do to help the situation?

I'm rather disappointed with various churches in the West. I especially think that the Latvian Lutheran Church abroad has been very narrow-minded on the issue. Only two people have said anything openly against the aggression against gays here, the Dean of the LELC in Sweden, Ieva Graufelde, and a Lutheran pastor from Britain, Jana Jeruma-Grinberga. I find it ironic that people who have been raised under democracy outside of Latvia now allow this country to live under totalitarian thinking. They keep quiet, but even a simple letter to a local newspaper encouraging the church to keep peace here could stop a lot of aggression. Latvians still listen to authority figures.

How long to you think it will take for things to normalise here? When will two gay men be able to walk down a Latvian street holding hands, without people shouting at them?

Two gay men cannot walk down the street holding hands anywhere in this world. In New York City you can also be beaten up because of that kind of openness; even in Stockholm. Maybe a more appropriate indicator of 'normalisation' would be when we have a partnership law here. I think that could happen within eight years…possibly sooner.

If this happens, would you consider returning home? Or are you leaving Latvia for other reasons as well; to get away from other bad memories?

My memories about Latvia are not only of the last six years. I grew up here, I love Latvian culture. I really enjoy walking in our unspoiled nature. I would love to come back, even though I do have some bad memories. As for when I might return…probably when we have this partnership law; only then I could come back.

Being a public figure, you've suffered many attacks. How often has this happened to you, and how have you dealt with this hate?

The most difficult period was after Pride 2006, because as I said, Latvians always listen to authorities. I had about ten attacks in one year. Most of them weren't physical, except the one time some people tried to drag me into a courtyard, but I escaped. There was also one break-in at the church. After last year's Pride, when the message to society was that the police were protecting Pride and the peoples' rights, almost no one tried to approach me physically. How do I deal with it? I think that I am coping quite well. Sometimes I cry, sometimes I smoke, or I go to psychotherapy. But now I am fed up with all of this, I don't want it any more. It's more difficult for me when my mother is verbally attacked; she had some very difficult situations in her hometown. Once my son was threatened on the Internet. At these moments I feel absolutely terrible.

Your family seems very supportive of you, what do they think about you leaving?

They are sad, of course, but my mom says, "Go, go, go…you should go".

What advice do you have for young gay men and women here who can't leave, don't have the option to go, don't have the money or don't speak other languages? What advice would you give these people?

I would advise them to look into their resources, because sometimes we think we don't have anything, but actually we do. Sometimes it's just a matter of contacting Mozaika, or even the Individual Psychological Institute, because they have made a psychologist's group who are specially educated to work with LGBT people. If the person doesn't have enough resources, they should be very, very careful about coming out. And when they do come out, they should only do so to people who they really know love them.

Why do you think that it's so hard for Latvians to accept homosexuality?

There was a survey published a year ago, that 1/3 of Latvians are homophobic and hostile toward gays, 1/3 are indifferent, and 1/3 are willing to support of gays. I think most Latvians are very insecure with their ego, and they feel that the Latvian identity is somehow threatened by homosexuals.

Will you come back for Pride next year?

Yes, I am planning on it.

What are you most looking forward to about living in London?

I am very excited about working with British clients as a psychotherapist, because the psychotherapy tradition in the United Kingdom is totally different than in Latvia. People go to psychotherapists not only when they are at their last rope. They understand that they have difficulties that they need to solve much earlier. So that means that I get people earlier, and we have more chances to work through their difficulties.

The decision to leave one's country is always difficult, but given the current situation for minorities here in Latvia, it is understandable why one would make this choice. On June 15th, Maris celebrated his last church service with his congregation at the Anglican Church in Riga amid many tears, smiles and hugs. His congregation presented him with a shiny new suitcase, to travel safely both from and back to Riga. On June 18th, he boarded his flight for London, and said goodbye to his homeland. Who knows what the future holds for Maris; for now we wish him luck in his future endeavours, and we hope to see him in Latvia again someday.

By Amy Bryzgel